Town Hall Through a Crisis Communications Lens

🫏 Hack Mule Case Study

Kudos to Montgomery County Council Member Evan Glass (At Large) for convening Saturday’s Transportation Town Hall in Rockville.

I attended expecting to hear the same complaints people in my neighborhood raise all the time: slow traffic, trigger-happy red-light cameras, and a perennial favorite, the seldom-used bike lanes on Old Georgetown Road.

Instead, I sat through a case study in crisis communications as officials faced aggrieved — and grieving — residents who wanted action and answers.

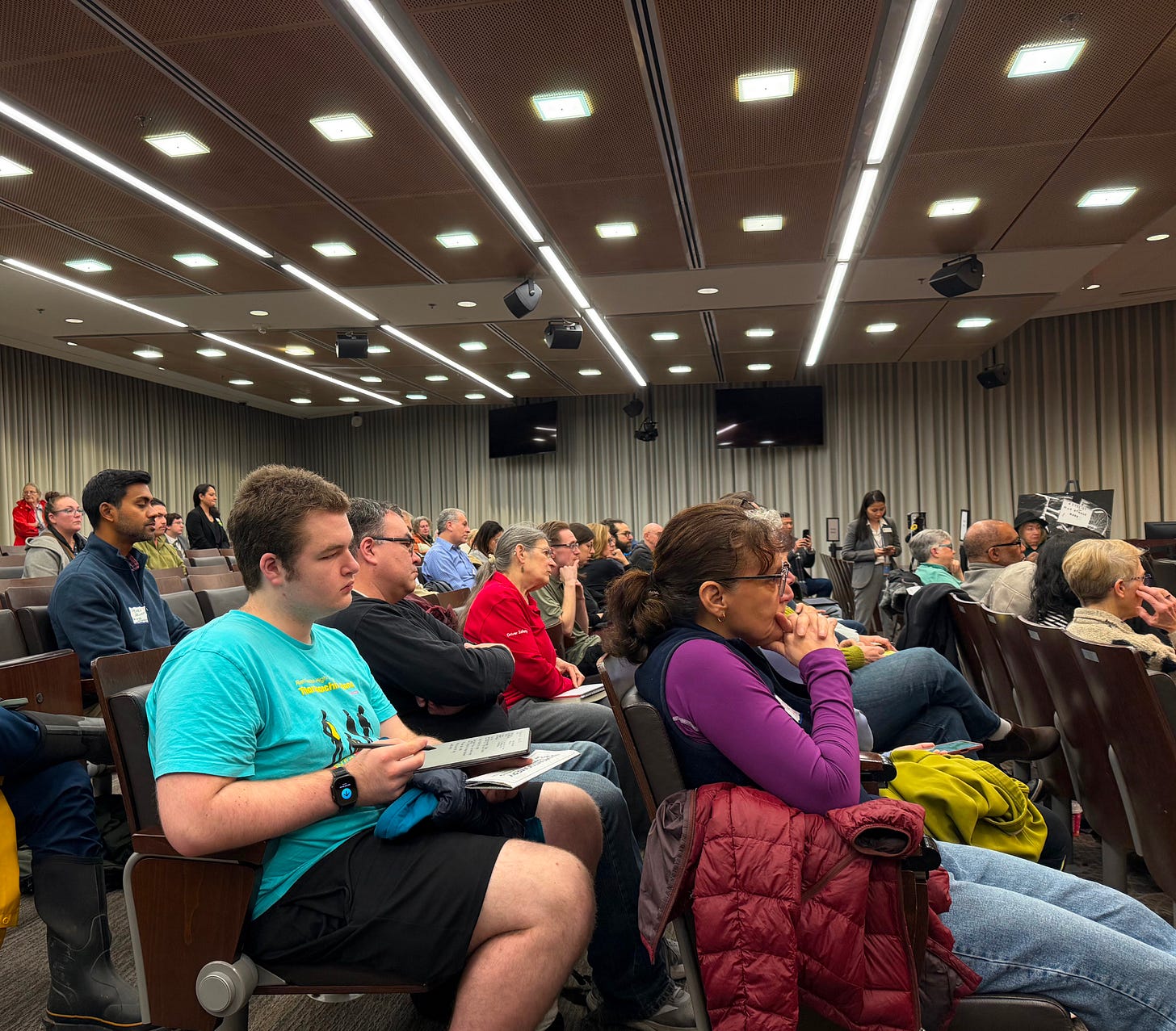

The fact that the 225-seat Council Hearing Room was standing-room-only at 10 a.m. on a cold, rainy Saturday morning was my first clue about just how much county residents wanted to make their voices heard.

Glass gathered a dozen officials from the transportation department, the police, and other agencies for large-group breakout sessions on county-road safety, state-road safety, and school-related safety issues.

After opening remarks and introductions, Glass clearly read the room, declaring that no one would be giving PowerPoints. “We want to hear from the people,” he said.

It was a good message to inject at that point — no one gets up early on a Saturday morning for a policy briefing.

I opted for the breakout session on county roads moderated by Montgomery County Department of Transportation Director Christopher Conklin, supported by Montgomery County Police Assistant Chief David McBain, whose mission includes traffic and road safety.

The two spoke for a few minutes about statistics relevant to their programs. They’re both excellent speakers, and they’ve obviously presented about safety many times. They even have “stump slogans.” Conklin, for instance, said DOT has shifted from “what is the fastest” to “what is the safest.”

(As a county driver, I would have guessed they had shifted to “what is most likely to make drivers lose the will to live,” but safety is a nice goal, too.)

McBain said he believes in the “Three E’s” of transportation safety: engineering, education, and enforcement.

OK, that works. Please carry on.

Then they opened the floor to questions. The first few were softballs about parking in bike lanes, expanding driver education, and improving the “walk shed” around Purple Line stations.

But that tension in the audience during the opening was still there.

I could feel the room’s emotional temperature rising when a mother whose young son was hit by a car in front of her house complained that police weren’t being aggressive enough. Even worse, she said, thanks to Google Maps, drivers know her street is just outside a school zone, and they use it as a high-speed cut-through.

McBain responded clearly with comments about “high-incidence zones,” automated cameras, and graduated fines, but he didn’t meet her concerns with much empathy.

Warning bells were going off in my communicator brain. “Danger…danger…”

After a few more utility questions about budgets, lane narrowing, and daytime running lights, another woman got up and said she had lost her son in a crash. Her voice cracked as she complained that the county is paying too much attention to data “after the fact” and not enough to prevention. Her anger bubbled up as she went on to cite other fatalities.

This moment was “game over” for the panel. It’s the worst-case scenario I’ve taught my clients about for years — you cannot overcome an emotional mother who has lost a child. You must empathize, validate her concerns, and show compassion. Never lead with data, because she — and the rest of the audience — have only one data point in mind: One dead child.

On seeing nods and hearing murmurs, I’d have been tempted to ask the audience if anyone else present had experienced a similar tragedy. You might as well release the tension and let people tell their stories at that point.

Show compassion, offer resources. It would have been a great moment to stand up, grab a mic, and walk to the audience. Align yourself with the audience by coming to the same level, literally.

McBain started by expressing his condolences for her loss — absolutely the right move — but he went on to explain that the police don’t want to “put cameras where people tell them to put them.” They rely on data only, because it’s objective.

Conklin answered with jargon about “always-stop controls.”

Those are undoubtedly correct and relevant answers, but in this moment, not answering might have been even better. But it didn’t matter — people weren’t listening anymore. Everyone was turned in their seats to console the woman.

The next speaker was a blind woman who explained that due to problems with sidewalks and crosswalks, she can no longer navigate to her bus.

That pulled at the heartstrings, too. Conklin asked her for more information so he could look into it.

OK, solid response.

Next was a mother whose child was hit by a car on her cul-de-sac — she wanted to know why promised changes on her street were stalled. The officials promised to look into it.

Then came a man who witnessed a child struck and killed — why hadn’t changes happened in that neighborhood? Conklin explained that area is not a “Tier 1 priority.”

At this point, every communications-consultant instinct I have was telling me to get up, pull the fire alarm, and evacuate the building: “Tier 1 priority” should never exist in response to “child struck and killed.”

Simple as that. It is a null response.

A vision-impaired man then spoke about how he also has trouble with crosswalks and buses. When he urged officials to make the transportation system workable, he added, “Because disabled people can’t afford ride-shares everywhere!”

By now, people were calling out from the audience in support. The dam was leaking.

After a few calmer questions, we heard from a blind woman who had been hit by a car. That was bad enough, but her bigger issue was that the Braille signs at Woodmont and Bethesda Avenue in downtown Bethesda are mounted backwards and upside-down. They literally send people down the wrong road in the opposite direction.

That is a textbook example of how not communicating can sometimes be more helpful than communicating badly. Painfully bad.

Conklin and McBain did many things right: they stayed calm, they gave clear answers, and they explained their topics precisely. But by not honoring the emotions more, they missed an opportunity to keep concerned citizens from turning into angry opponents.

People sometimes wonder why speed limits are dropping and bike lanes are expanding. The answer is that no one is advocating for cars. Instead, officials are hearing devastating stories like these and reacting to them — not in the moment, but, consistently, through policy.

Quite a way to spend Saturday morning.

One of your best! Insights without anger, but still made me angry- at their lack of sympathy and solutions.