The Bethesda Meeting House

🫏 Hack Mule Field Trip to the Church that Named a Town

I’ve driven up and down Rockville Pike literally about 15,000 times over the years, and I’ve often wondered about the story behind the Bethesda Meeting House, the little white church perched on a bluff between the Capital Beltway and Cedar Lane.

Signs for the “Church that Named Bethesda” have been around for as long as I can remember, but no one ever seemed to know the history. How did this little church outlast developers, planners, and road crews for 200 years? And, what’s going on there now?

Last Sunday, Bethesda Historical Society President Wendy Kaufman filled me in on the details and gave me a tour of the church and the parsonage next door.

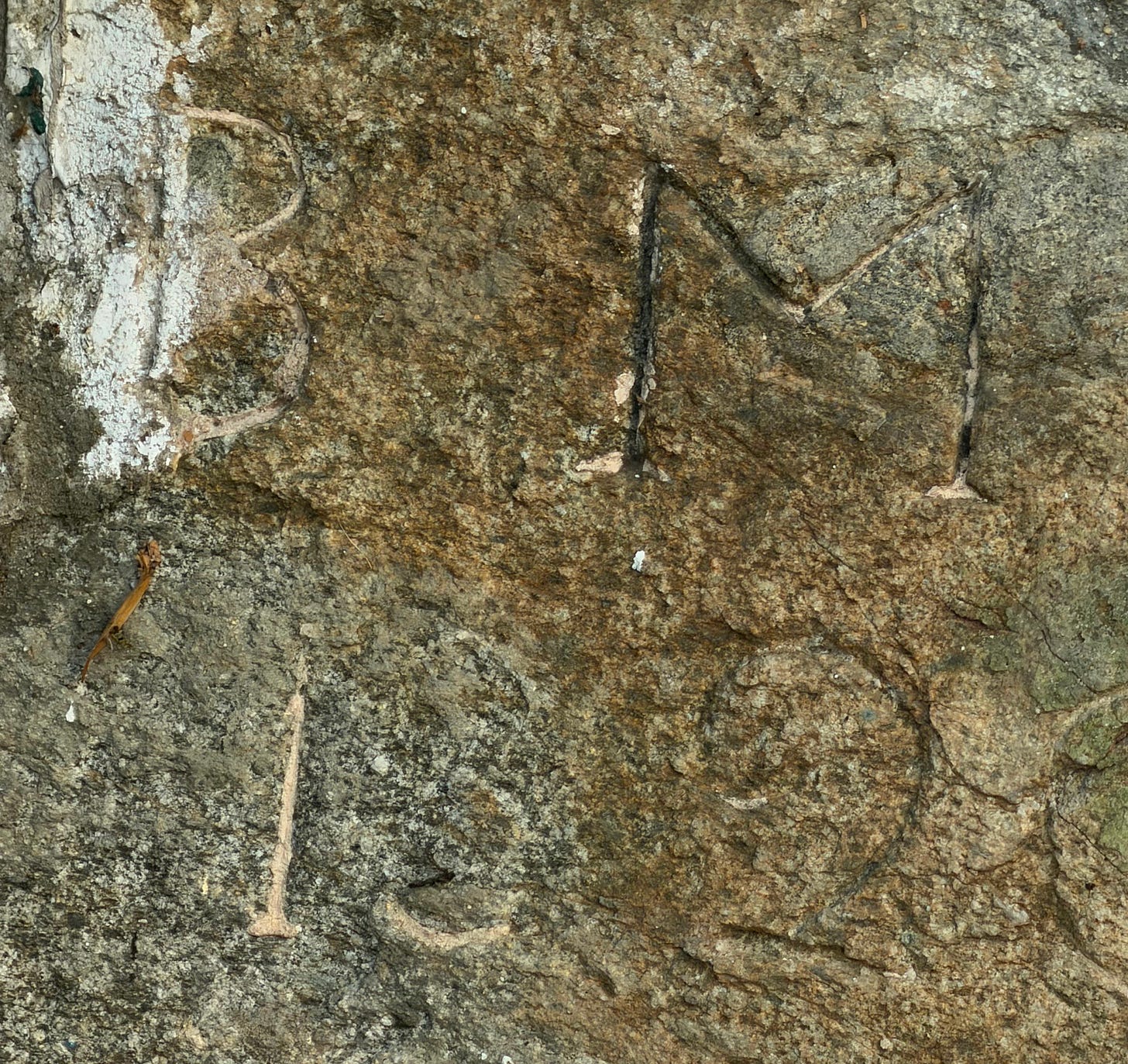

The site dates back to 1820, when a Presbyterian congregation built a church to serve Darcy’s Store, as the town was known back then. A fire in 1849 destroyed the original building, but the congregation rebuilt on the same site, even preserving the original cornerstone.

The church prospered, and by 1871 the pastor was influential enough to prevail on the local postmaster to rename the town Bethesda, in honor of his employer.

So, for those who are keeping score, we now know that Bethesda literally arose from a lobbying deal by a special interest group. La plus ça change…

In 1925, the Presbyterians built a new church on Wilson Lane and sold the Meeting House to a local socialite who used it as a home and art studio. She lived there until 1945, when she sold it to a Catholic missionary group. They held it until the 1950s, when it became the Temple Hill Baptist Church.

Over the years, the Temple Hill group dwindled, and the site fell into disrepair. But in late 2023, thanks to a generous benefactor, the Historical Society purchased the complex and created the new Bethesda Meeting House Foundation (BMHF).

It’s exciting news — as every native Washingtonian knows, when a project gets a foundation and an acronym, it is destined for greatness.

BMHF has started the painstaking process of restoring the church and the parsonage, both of which are on the National Register of Historic Places and the Montgomery County Master Plan for Historic Preservation.

The parsonage, also from the 1850s, struck me as a bit of a mash-up — a little Victorian, with a few Queen Anne flourishes to brighten it up. I’m picturing the church elders trying to go cheap on building but adding some fancy dressing for an upscale gloss.

(As the stepdaughter of an Episcopal minister, I can attest it’s no coincidence that “parsonage” and “parsimony” share a root.)

Even the narrow interior staircase, with two quick 90-degree turns, screams “thrift” — I mean, Benevolent Dead Churchmen of 1850, could you not have bumped out the wall just a few feet so the pastor and his family didn’t have to play human Tetris to get upstairs?

But the parsonage has some interesting period details, such as stained glass windows and a giant gravity-heat register in the middle of the main floor. (Perhaps the family was too busy huddling around the grate for warmth to bother going upstairs.)

The parsonage is also a time capsule of family life — old board games tucked under a record player, a huge mahogany console housing an ancient TV and radio.

That’s the private side of life on this site — domestic, improvised, and nostalgic. To see the public side, you have to cross the gravel parking lot and walk along the newly uncovered carriage trail that leads to the Meeting House.

The Meeting House is a plain white clapboard church with few adornments apart from a cross on top — no bell tower, no steeple. It would look perfectly at home on a village green in New England. No self-respecting sinner would dare approach.

On closer look, though, I started to wonder if the 1850 congregation ordered the details à la carte during the annual meeting:

“Mildred, you wanted Gothic stained-glass windows, right? Fine. Frank and Trudie, you voted for a Greek Revival temple front — we can do that. And Clarence, don’t worry about the extra shutters from the parsonage. We’ll just hang them up next to the Gothic windows. No one will ever notice they’re the wrong size.”

Things are a little calmer inside, where nine rows of pews sit on either side of a central aisle that leads up a few steps to a modest lectern. The apse hangs cantilevered off the back of the building — why build a structural support when prayer and sobriety can do the heavy lifting for free?

The church also has a loft over the entryway that the National Registry application describes as a “slave gallery.” Although I’m no expert from an architectural or historical standpoint, I’m skeptical about this. The loft appears to be a later addition that covers part of the front windows and jams awkwardly against the side windows. It looks like an afterthought, not an original feature.

But perhaps that legacy connected to slavery is what gave rise to the story that Abraham Lincoln worshipped here. Lincoln did attend Presbyterian churches with his wife, so who knows?

Another legend is that Paul Revere cast the church’s bell. Wendy Kaufman was doubtful when I asked about it, and for good reason — Paul Revere died at age 83 in 1818, two years before the original church opened.

Still, legends add local color, even when they don’t quite check out.

Between digging through the historical record and tackling the sheer amount of restoration still ahead, the Bethesda Historical Society and the Bethesda Meeting House Foundation have their work cut out for them. They’re looking for volunteers, ideas, patience, and cash.

What the site ultimately becomes is still an open question. But perhaps that uncertainty is fitting. For more than two centuries, this place has adapted — from church to home to mission to quirky landmark — while the world rushed past it.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for Bethesda itself.